House energy committee signs off on push for federal support for New Mexico’s downwinders

New Mexico downwinders are hoping to have the state added to the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act before it sunsets in 2022.

Members of the House Energy, Environment and Natural Resources Committee were visibly distressed during a presentation about radiation exposure in New Mexico stemming from the 1945 Trinity nuclear bomb test and subsequent uranium mining that supported the federal nuclear program during World War II and the Cold War.

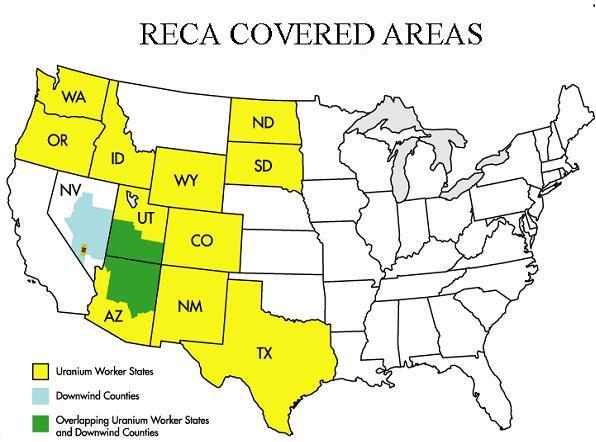

Rep. Angelica Rubio, D-Las Cruces, introduced House Memorial 5, which asks the congressional delegation to continue pushing for the state to be included in the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA).

“There was a lot of testing in our past, and New Mexicans have not been properly compensated, unlike other parts of the country,” Rubio said. “This memorial asks the legislature here to support us asking Congress to continue to push for this expansion and include our communities in the state of New Mexico.”

Source: U.S. Department of Justice

The lingering impacts of that exposure still present problems for New Mexican families today, said Tina Cordova, co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium. Cordova served as Rubio’s expert witness during the meeting.

“I am also a downwinder, I was born and raised in Tularosa, and I am a cancer survivor,” Cordova said. “I was diagnosed with cancer when I was 39 years old. The first question they asked me was ‘when were you exposed to radiation?’”

The Tularosa downwinders group was organized 15 years ago to bring attention to the negative health impacts suffered by the people in New Mexico as a result of the above ground testing that took place at the Trinity site in 1945, Cordova said.

The federal government has been reluctant to acknowledge any impacts of the test on New Mexicans. The Trinity test, conducted near Alamogordo in what is now White Sands National Park, was the first nuclear bomb test in the world. The test was conducted in secrecy during World War II. Reports indicate the government did not alert surrounding communities to the test ahead of time, and no evacuations were performed.

“The people of New Mexico likely received 100 times more exposure than anyone ever did in Nevada,” Cordova said. “Exposure to radiation is a factor of distance and time. If you live closer to a test site, you receive more exposure.”

She pointed to Winslow, Arizona, which is included in RECA as a downwind community from the Nevada test site.

“Winslow is 280 miles from the test site,” she said. “We have families living as close as 12 miles from the test site here in New Mexico.”

“There’s been absolutely no study that we know of on the effects of the population in New Mexico, whereas there’s been extensive studies of the populations in Chernobyl, Fukushima, and even Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” she said.

Committee members weigh inDuring the somber presentation, a few members of the committee shared their own personal experiences with radiation exposure related to the Trinity test and uranium mining.

“I lost a father-in-law in his early sixties because he worked as a geologist with the uranium mines; and also a brother, who died at 44 because of cancer, who also worked in the mines,” said Rep. Joanne Ferrary, D-Las Cruces.

Rep. Phelps Anderson, R-Roswell, said his own mother witnessed the bomb test.

“In the early, pre-dawn darkness, she was making coffee in the kitchen of a cabin in the Sacramento Mountains and all of the sudden the room lit up, and she thought it was [a truck’s] headlights. She looked out the window and there was no pickup truck,” Anderson said. “My mother often said that’s the day her hair turned white, and she was a young woman.”

“I’m not here to confirm or deny that, I’m just repeating the story I grew up with,” he added.

Rep. Joseph Sanchez, D-Alcalde, who was waiting to present his own bill to the committee, underscored the importance of the issue to New Mexicans across the state.

“Over the past eight months I’ve been driving all over the top half of the state, and this is a huge issue,” Sanchez said. “People that were exposed to this have not been taken care of.”

Representatives from advocacy groups such as Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety, the Sierra Club, the Multi-Cultural Alliance for a Safe Environment, Interfaith Worker Justice New Mexico, Retake Democracy, and Health Action New Mexico all voiced support for the memorial. Time is running out!

The push to add New Mexico to RECA hasn’t gained any traction at the federal level, despite widespread support for the initiative among New Mexico’s congressional delegation over the last decade.

“This is the tenth year we’ve had bills to amend the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act entered into Congress, both in the House and the Senate, and we’ve only seen one hearing in the Senate Judiciary in 2018, which is problematic because, without hearings these bills cannot advance,” Cordova said.

There are currently two bills introduced that would expand RECA to include communities in New Mexico and in other states. House Resolution 3783, was introduced by U.S. Rep. Ben Ray Luján in July 2019. That bill has been sitting in the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties since August. Senate Bill 947, co-sponsored by both New Mexico U.S. Sens. Tom Udall and Martin Heinrich, has been sitting in the Senate Judiciary Committee since March 2019.

But time is running out for New Mexico to be added to the compensation program. RECA is slated to sunset in 2022.

Cordova said if RECA sunsets before any new amendments are passed, the downwinders will have to start from scratch on the bill and secure an ongoing funding source. The current RECA law has a permanent funding source.

“Those sorts of bills are very, very difficult to get passed these days,” Cordova said.

In the meantime, RECA has paid out $2.3 billion to downwinders in parts of Nevada, Colorado and Arizona.

“It provided them with healthcare coverage, which is actually what we covet most,” Cordova said. “Most of the people affected by this live in rural areas and are underinsured or uninsured, and have a lack of access to healthcare coverage, so they usually get diagnosed much later in their disease process, which reduces their prognosis.”

Rep. Rod Montoya, R-Farmington, asked why the amendment to include New Mexico hasn’t been adopted in ten years.

“The answer that’s most commonly given to us is that they don’t believe they have the resources to fund this further to include additional downwinders,” Cordova said. “One of the things we’ve been told is that they believe the claims are going to be significant coming out of the state of New Mexico.”

Rep. James Strickler, R-Farmington, asked why New Mexico was left out of the 1990 RECA bill.

“That’s the $2.3 billion question that we may likely never know the answer to,” Cordova said.

The memorial passed the committee unanimously. It will head to the House floor next.